This year, we celebrate a milestone for Lady Elliot Island. Constructed in 1873, our charismatic light house has stood tall, steering sailors in the right direction for countless years. This blog will explore the life of the lighthouse, some of the key figures involved and the celebration in store for 2023!

A journey through time…

1816

Lady Elliot’s Island was named by “The Lady Elliot” – a ship on its maiden voyage from India to Sydney.

An artwork from the early 1800’s showing low growing vegetation and birdlife dominating the landscape.

1819

Saw the first surveying voyage of the Capricorn Bunker group by Captain Phillip King.

He described the island as such:

“LADY ELLlOT’S ISLAND is a low islet, covered with shrubs and trees, and surrounded by a coral reef, which extends for three-quarters of a mile from its north-east end; the island is not more than three-quarters of a mile long, and about a quarter of a mile broad; it is dangerous to approach at night, from being very low” – Captain Phillip King (King, 1825).

1860

1866

1872

The temporary light was damaged in a storm, which gave the guano miners a chance to remind the government that a more suitable lighthouse was needed:

The government realised the urgent need for a light station on the small island. Tenders for the construction of a permanent lighthouse were called immediately to close on 28 June 1872 and after two rounds of tendering, the building contractors John and Jacob Rooney of Maryborough, who had already erected the lighthouse at Sandy Cape, were the successful tenders for the sum of £1549 (Thorburn, 1967).

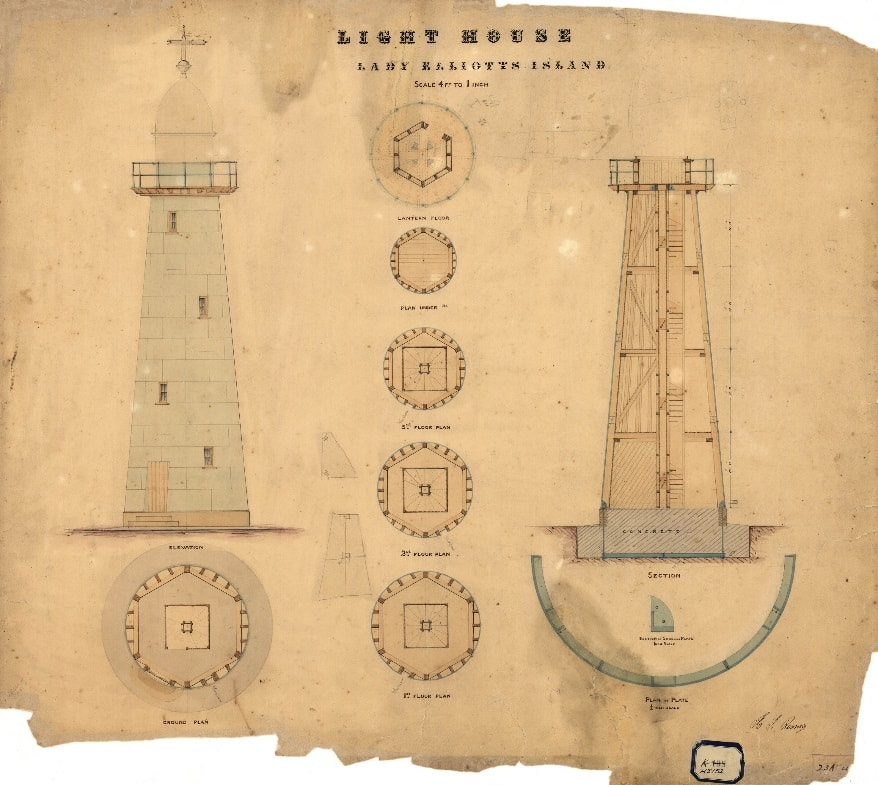

Contract drawing of Lady Elliot Island lighthouse, signed in 1872 (National Australian Archives: J2775, HS152)

1873

Captain Heath reported in 1873 that the temporary light on Lady Elliot Island had been replaced by a tower forty-five feet high, the frame strongly constructed of hardwood, plated with 18-guage galvanised iron; the whole building stood upon a concrete foundation.

The light was a revolving light of the fourth order, which though small, was almost equal in brilliancy during its flashes, which are at intervals of half-a-minute, to a second order fixed light, and answers well the purpose for which it is intended.

He also advised that it had been necessary to place a second light keeper on the Island as the Australian Guano Company had withdrawn the man who was in charge of the island who acted as occasional light keeper (Thorburn, 1967).

Alongside the lighthouse, two cottages were constructed for the lighthouse keepers and their families.

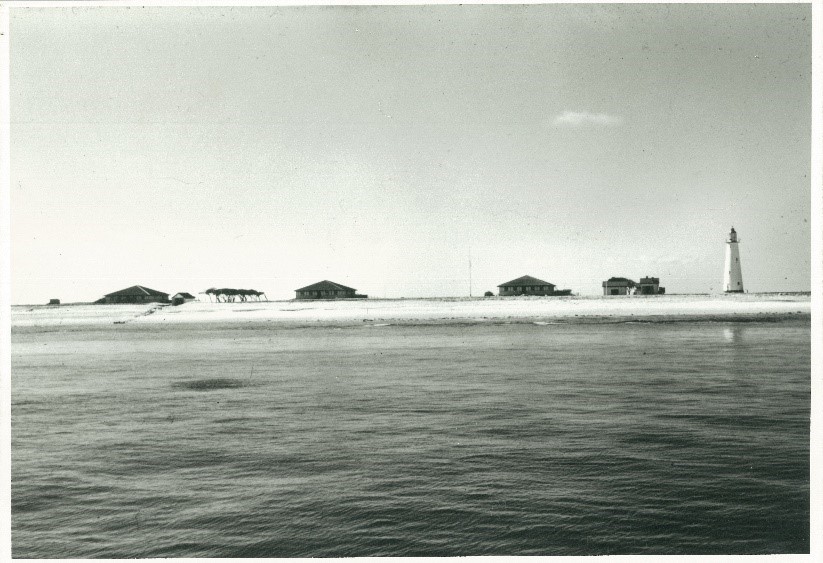

Lady Elliot Island lighthouse and cottage, undated (Source: Australian Maritime Safety Authority)

The lighthouse was operated by the Queensland Department of Harbours and Rivers until the Commonwealth Lighthouse Service was established (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012). The weight mechanism fell 22 feet per hour with a maximum fall of 40 feet, meaning the keepers would need to wind every two hours (Chance Brothers & Co Limited).

Robert Lucas Chance of the Chance brothers

A look inside the lighthouse in modern times; the small wooden door houses the falling weight which needed to be re-wound every two hours.

The two original lighthouse keeper’s cottages built in 1873

1920’s

In the 1920’s the two original lighthouse keeper cottages were demolished, and construction began on three more raised, 5-bedroom, weather board houses. A boat shed, lighthouse maintenance shed, and storage shed were also built by 1927.

The boat shed had wrought iron tracks which used to carry long boats to meet the supply vessels and ferried back and forth to the storage shed with the aid of a winch.

A major overhaul of the light house began as well, the optical apparatus, the lantern and the balcony/lantern-room floor were all replaced. The new optical apparatus supplied by Chance Brothers & Co included a mercury pedestal – a form of low-friction bearing first used in Australia in 1896 at Cape Leeuwin – which required less maintenance than earlier types. There was a new fourth order (250mm focal radius) catadioptric lens assembly, with three single-flashing faces. The light output, from an incandescent kerosene burner, was rated at 85,000 candlepower (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012).

1923

1950’s

The Cape Leeuwin was the supply ship to Lady Elliot Island. Built in 1924 for the lighthouse service, the ship was requisitioned for military service by RAN in 1941 and served with her original captain until 1945 when she was returned to her owners and kept in service until 1963.

HMAS Cape Leeuwin – Australian National Maritime Museum

“The first time I saw the island from the lighthouse ship Cape Leeuwin, I thought we had been sent to the end of the earth. Once ashore and finding the abundance of nature, we realised it was one of the most delightful places to live.”

– Charlotte Wright, wife of Jim Wright, Lighthouse Keeper, Lady Elliot Island 1961–1965

The three lighthouse keepers’ cottages constructed in place of the two original cottages. These three cottages still stand today.

1960’s

The keepers and their families received fresh food and other supplies by boat from Bundaberg each fortnight (AMSA 1962). They used rainwater for drinking and washing and kept chickens and goats for fresh eggs and milk. Their lives were made a little more comfortable when a diesel generator was installed to provide power to the houses.

The lighthouse, storage shed and generator shed. www.lighthouses.org.au

“Mum would always be baking, to feed the keepers, families, and any workers. There were always fresh cakes, or fresh biscuits and fresh bread straight out of the oven with butter and vegemite – it didn’t help with the waistline!”

– Peter Braid, son of Head Keeper Gordon Braid, Lady Elliot Island 1978–1980

1973

The lantern was removed from the lighthouse and replaced with a Chance Brothers and Company lantern with curved glazing, vertical astragals, and a drum type (admiralty pattern) roof vent. The balcony floor structure was removed and replaced by the present assembly of mild steel plate floor supported on rolled steel channel beams. The present steel balcony balustrade was also installed (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012).

“In 1979 the salary for a light keeper was $16,000 – which is equivalent to $73,000 today”.

“There was a lick of stress, you couldn’t ask for a much better job or way of life.”

– Peter Braid, son of Head Keeper Gordon Braid, Lady Elliot Island 1978-1980.

“I always loved the romance of the kerosene light; you had a feeling of just being. I loved the mateship, the comradery, people were always willing to help, and family – the kids grew up there, we taught them school”

– John Denman, Lighthouse Keeper, Lady Elliot Island 1974–1976

1980

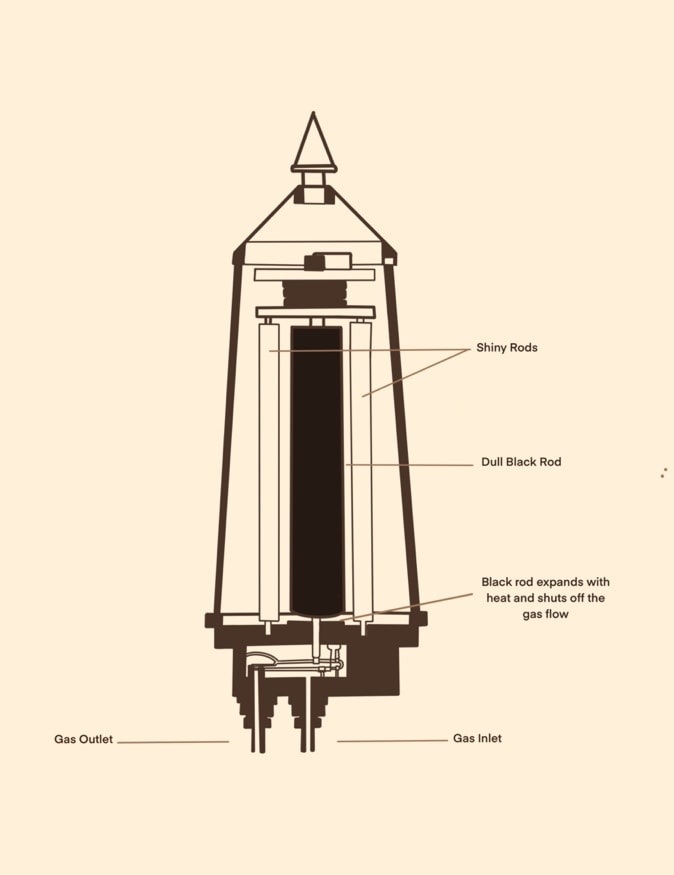

The lighthouse Acetylene conversion and automation began in 1980. The lighthouse was converted from kerosene to acetylene operation. This involved extensive changes to the optical apparatus, in which only the 1927 Chance Brothers & Company lens assembly was retained.

The mercury pedestal and clock were removed and replaced with an AGA Dalen rotating pedestal type PRDA-120. The PRDA-120 used the flow of gas to rotate the lens very slowly during the day so that the sun would not be focused by the lens and start a fire, and after dark at the right speed for the apparatus to show the correct character. A Dalen sun valve sensed the onset of darkness and lit the incandescent burner which burned constantly through the night. At sunrise the gas flow was automatically cut off by the sun valve, except for a small pilot flame.4 A man-proof fence was built around the tower and former generator shed.

“Boats knew when they passed that light, that someone was always

there. In bad weather, rough weather, we were there”

– John Denman, Lighthouse Keeper, Lady Elliot Island 1974–1976

A Dalen Sun Valve, installed in the 1980’s.

1981

By January, the lighthouse was now converted, the lighthouse could operate automatically without human intervention. Only periodic service visits were required to replace gas bottles and to check the equipment.

The keepers were withdrawn from Lady Elliot Island after staff of the resort (opened in 1984) had been trained to record and report weather observations (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012).

1988

Lightkeepers remained until ~1988 to collect weather reports and perform caretaker duties.

1995

A new light tower was erected on the island.

2004

The lighthouse and associated buildings all received a heritage listing and all remain in-tact and freshly painted presently!

“A Prototype for Queensland”

The lighthouse at Lady Elliot was the prototype for a new style of construction that was subsequently used along the Queensland coast and another eleven of the same basic type were built up until 1890. They were all fitted with Chance Brothers optical apparatus, ranging in scale from 2nd order (700mm focal radius) to the 4th order (250mm focal radius.)

Robert Ferguson was an architect working at the office of FDG Stanley – superintendant of public buildings, and was a district foreman of works. Ferguson had written the specifications and oversaw the assembly of the iron lighthouses at Bustard Head and Sandy Cape and was also credited for the design of the light station at Lady Elliot Island. For Lady Elliot, Ferguson designed a composite form of construction, combining the economy of timber framing with weatherproof and durable iron plating on the outside.

Stanley reported to the government on the new design:

“On connection with the Tower, as to construction and material, I would beg to remark that while the present design is more costly than the original, which was similar to those erected on Woody Island and entirely of timber, it is submitted that the increased strength and durability gained by using boiler plate casing, concrete foundation etc. will eventually more than compensate for the greater outlay in the first instance, the shrinkage and decay of timber sheeting in exposed situations such as the Lighthouse will occupy, being so great, as to render it almost impossible to keep the buildings weatherproof. Added to this the destruction caused by the white ant to all timbers placed below or upon the ground, is such as to render it most desirable, that every means should be used to place timber framing as far as possible beyond their reach” (Thorburn, 1967).

The tapering outer walls were framed with sawn hardwood posts and rails, bolted together with joints reinforced with wrought iron straps and brackets. The walls were lightly braced by timber braces which would have served to stabilise the timber structure before the iron shell was fitted. There were three intermediate floors with hardwood joists and pine floorboards. In the centre of the tower was a vertical timber weight tube, which formed a central support for a winding timber stair that ran up the bottom three levels of the tower. On the fourth level, where the conical tower was too small to fit a stair, there was a fixed ladder up to the level of the light room and balcony. The frame was supported at the bottom by a segmented cast iron ring that formed a base, bolted to a massive concrete footing and floor cast within a low stone wall. The tower was clad with a covering of wrought iron plates, about 2.5 mm thick, which were rolled to conform to the conical shape. The metal plating at Lady Elliot Island is wrought iron plate, measuring about 2.5 mm thick (12 gauge). Wrought iron plate is a distinctly different material from the cast iron used for the earlier towers at Bustard Head (first lit in 1868) and Sandy Cape (1870) with tower walls about 30 mm thick. The wrought iron plate was manufactured in England and shipped to Australia as flat sheets. The building contractors cut each plate to the correct outline and curved it to fit the conical shape of the tower. The plates were lapped and riveted and screwed to the timber framework and to the iron ring at the base. A timber door was fitted at the bottom of the tower, and glazed windows at each floor level. At the top of the tower was a timber-framed structure, which formed the floor of the lantern room, and the projecting balcony that surrounded the lantern room. This balcony floor probably had a flooring of timber boards with a waterproof covering of lead sheet (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012).

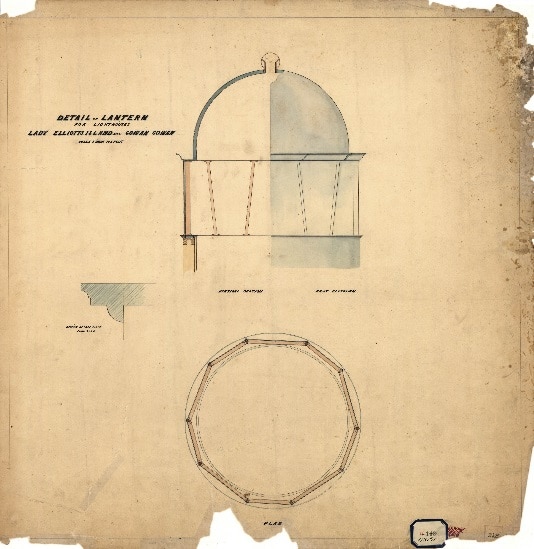

The lantern (the structure which enclosed the lantern room, and which protected the optical apparatus) had three main parts, as follows. The base (sometimes called the murette) was hexagonal in plan, framed in timber, clad with iron on the outside. There was a low door in the base through which the keeper could crawl out onto the balcony. Above the base was the glazed section, also hexagonal in plan, with glass panes in a slender framework of iron. On top was the lantern roof (sometimes called a dome or cupola) of metal sheeting on an iron frame, with six facets curved to form a dome. At the peak of the roof was a weatherproof vent for the lamp smoke to escape. All of the parts just described were locally made in Queensland. Inside the lantern room was mounted the optical apparatus, manufactured by Chance Brothers & Company, lighthouse engineers, in their factory at Smethwick near Birmingham, UK. The apparatus consisted of a rotating lens assembly of 250 mm focal radius which concentrated the light from a kerosene wick burner into several rays of light. As the lens assembly was slowly rotated by a clockwork (powered by a weight descending in the weight tube) the rays of light travelled around the horizon, showing an intense flash of white light of 4,000 candlepower every 30 seconds to a navigator on a ship (GBRMPA, Reichelt , 2012).

2023

Further reading and resources:

- https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/retrieve/221786f4-a6ea-4c75-8f48-edceb5374590/Lady%20Elliot%20Lightstation%20Heritage%20Mangement%20Plan%2B%20explan%20statement.pdf

- Lady Elliot Island Lighthouse | Lighthouses of Australia Inc.

- Australian Heritage Database (environment.gov.au)

- Lady Elliot Island – first on the Great Barrier Reef – Official website (archive.org)

References:

- Australian Maritime Safety Authority 1962, ‘Lady Elliot Island Lighthouse Maintenance Records 1952-62’, Unpublished report, to AMSA, Canberra.

- J. H. Thorburn, “Major lighthouses of Queensland,” Queensland Heritage 1, no. 6 (1967): 24; “Arrival of the SS Sunfoo,” Brisbane Courier, December 13, 1873,

- Chance Brothers and Company Limited n.d. a , Lady Elliot Isle. General Arrangement of 4th Order Apparatus, Chance Brothers and Company Limited, Lighthouse Engineers, Smethwick, Birmingham. Australian Maritime Safety Authority drawing CN09-053-01[1].TIF.

- Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority 2005, Home Page, GBRMPA, Townsville, viewed 10/8/2011.

Snorkel & Dive

Snorkel & Dive Sustainability

Sustainability